- Home

- |

- About Us

- |

- Working Groups

- |

- News

- |

- Rankings

- WEF-Global Competitiveness Report

- Ease of Doing Business Report

- IMD-World Competitiveness Yearbook

- TI-Corruption Perceptions Index

- HF-Economic Freedom Index

- WEF-Global Information Technology Report

- WEF-Travel and Tourism Report

- WIPO-Global Innovation Index

- WB-Logistics Performance Index

- FFP-Fragile States Index

- WEF-Global Enabling Trade Report

- WEF-Global Gender Gap Report

- Gallery

- |

- Downloads

- |

- Contact Us

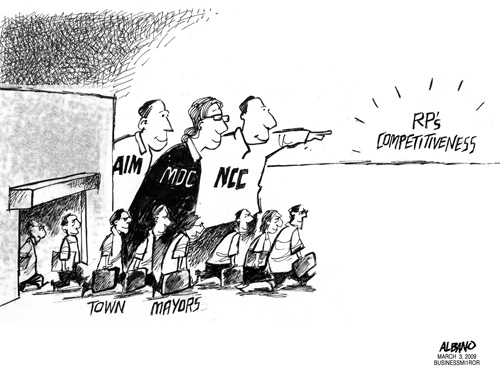

Spark plugs

HOW do you turn into good economic managers the country’s 1,499 town mayors, with close to 50 percent of them neophytes and about 10 percent not having completed elementary school? This is the tough challenge faced by the Mayors’ Development Center (MDC) and the National Competitiveness Council (NCC).

Thus began this paper’s front-page story in the Monday issue, on the bold—but crucial—initiative of the MDC, under former Angono mayor Gerardo Calderon, and the NCC—with plenty of help from an entity with solid track record in training for governance, the Asian Institute of Management.

Making towns competitive as economic havens in what everyone concedes to be a crisis year—nay, it’s going to be three difficult years, according to Albay Gov. and presidential adviser Joey Salceda—is by itself already a challenge. Ensuring that the towns are led by the “right stuff” who can steer them through the shoals of fiscal risks and economic collapse makes the task even more daunting.

It is important to train the town mayors because, as is obvious, not all local government units are lucky to have as much resources or be led by mayors of the caliber of Makati’s Jojo Binay, Taguig’s Freddie Tinga, Quezon City’s Sonny Belmonte or Parañaque’s Jun Bernabe. You’d know it really makes a difference to have a good mayor when you read Mayor Binay’s piece “Governance in a time of crisis” in this issue’s Perspective (page C1). We think his most important insight is the first of the three main ones he pitched, i.e. that while he is not an economist, he knows that “it is the people who make the economy work: investors, entrepreneurs, managers, professionals and workers. But they won’t come, and those already here will leave if our society keeps failing.” Amen.

If having the “right peopleware” is crucial then, what’s the challenge to the MDC? Calderon estimates that 700 of the current roster of mayors are serving their first terms, and probably 10 percent are “uneducated.”

There’s a silver lining in the first part of this situation—neophytes usually promise fresh winds of change, a certain creativity and an aggressiveness to prove they deserve their post. It also gives us some comfort, albeit not empirically confirmed, that somehow political dynasties (even assuming the neophytes are sons or kin of their predecessors) have been mellowed, and the era of warlords serving for 30 or 40 years is gone.

As for the lack of education of the 10 percent, Calderon puts it this way, “We know that they already have the heart to lead their community but we still need to upgrade their managerial skills, even down to the basic knowledge of how to manage their day-to-day in office.”

The training program has been such a hit that more than 400 of the neophyte local chief executives are already taking the short courses, envisioned to transform mayors from the traditional mold of planners and leaders to the developmental.

A simple but important example: Mayors in the traditional mold tend to rely mainly on their Internal Revenue Allotments (IRA), and when the budget falls short, they get money from their own pockets to fill in the budgetary gaps. But the “developmental” mayors are trained to craft revenue-generating strategies so they can augment the IRA with funds from tax collections.

Calderon’s group has a simple goal: to make their annual budgets at least a mix of 50-percent IRA and 50-percent revenues.

These are towns with annual budgets of as low as P6 million (Kalayaan in Palawan) to as high as P400 million (Dasmariñas, Cavite). About 600 municipalities are still categorized as Third- to Sixth-Class towns, which means each one’s annual revenue is still below P40 million.

The basic training on good management will be followed with the preparation of economic blueprints, with the growth sectors focused on, for instance, agribusiness, mining, information technology, business-process outsourcing and tourism.

If at least 35 towns this year can become what Ambassador Cesar Bautista, cochairman of the NCC, calls economic “spark plugs” pumping up the country’s competitiveness as their number increases, that would be a viable start. In a crisis year at that, that would be quite a feat. -BusinessMirror